Hey everyone,

I wanted to put together a quick, friendly rundown of what it’s actually like to climb Everest from the Nepal side—the kind of stuff that’s useful to know if you’re thinking about it someday or just curious how it all works behind the scenes.

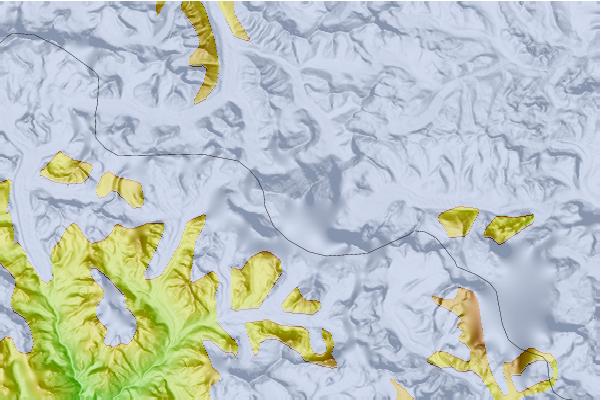

So first off, getting to Everest isn’t just “fly to Kathmandu and climb.” You fly to Lukla, which is that famously tiny mountaintop airport, and then you hike for over a week up the Khumbu Valley. Honestly, that part is beautiful—Sherpa villages, prayer flags everywhere, yaks with bells, and a mix of pine forests and huge mountains towering above you. Nights are in simple teahouses: wooden rooms, thin mattresses, and lots of dal bhat. Wi-Fi exists… sometimes… kind of.

By the time you reach Base Camp (~5,350 m), it already feels like a small tent city. Teams have massive dining tents, cooks, heaters, solar panels, and even espresso machines (depending on who you climb with). The glacier under the whole thing groans all night, and the sound of seracs cracking becomes weirdly normal. You end up living here for a month or more, going up and down the mountain to acclimatize.

The climb itself starts with the place everyone talks about: the Khumbu Icefall. It’s basically a frozen river of giant ice blocks slowly moving downhill. The route changes constantly. You walk across crevasses on aluminum ladders tied together with rope, and everything is held in place by fixed lines. This is one of the most dangerous parts, so you go through it early in the morning before the sun softens the ice.

Above the Icefall is Camp I, then a long, flat glacier valley called the Western Cwm, which feels like a solar oven. That leads to Camp II, where many teams spend a lot of acclimatization time. After that, the route gets serious on the Lhotse Face—hard blue ice at 40–50 degrees—which brings you to Camps III and IV.

Camp IV (South Col) feels like another planet. The wind is relentless, the air is brutally thin, and everything is loud, cold, and uncomfortable. This is where you switch to supplemental oxygen (unless you’re one of those ultra-elite no-O₂ climbers). Summit day usually starts around midnight. You climb in a long line of headlamps, and key landmarks like the Balcony, the South Summit, and the final ridge are absolutely unreal—narrow, exposed, and dramatic. The Hillary Step isn’t really the big block it once was, but the area is still steep and technical.

Reaching the top of Everest doesn’t feel like triumph as much as disbelief—and you only stay a few minutes, because the real goal is getting back down safe. The descent is just as tiring and, honestly, more mentally draining.

A few things I’d tell any friend:

Be in the best shape of your life. Everest is long, cold, and unforgiving.

Pick a good, experienced operator—it makes everything safer.

Acclimatize slowly; rushing is how people get hurt.

And above all: stay humble up there. The mountain doesn’t care how strong you are.